You Won’t Believe What York Hides on Its Quiet Streets

You know that feeling when you’re wandering a city and suddenly stumble on a view so quiet, so stunning, it stops you in your tracks? That’s exactly what happened in York. Beyond the crowded Minster and tourist trails, I found secret vantage points most travelers never see—hidden courtyards, silent rooftops, and ancient alleyways framing the city like a living postcard. This isn’t just sightseeing. It’s soul-stirring. And trust me, York saves its best views for those who wander with curiosity.

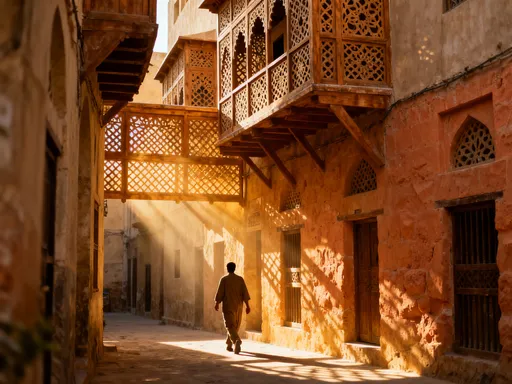

The Overlooked Magic of York’s Backstreets

Most visitors arrive in York with a checklist: photograph the Minster, walk The Shambles, visit the Jorvik Viking Centre. These are worthy experiences, to be sure, but they represent only one layer of the city’s character. The true magic of York often lies just beyond the footpath, in the network of narrow lanes and forgotten passages that twist between centuries-old buildings. These backstreets are not marked on most tourist maps, and they rarely appear in glossy travel brochures, yet they offer some of the most intimate and atmospheric glimpses of the city’s soul.

One such lane, tucked behind the bustling Coppergate shopping area, winds its way toward the River Ouse with barely a sign of modern life. Cobbled underfoot and lined with timber-framed houses leaning gently with age, this path feels like stepping into a different era. Sunlight filters through high stone walls at odd angles, creating pockets of warmth and shadow that shift with the hour. There are no souvenir shops here, no recorded audio guides—just the soft echo of footsteps and the occasional rustle of ivy caught in the breeze.

What makes these quiet streets so powerful is not just their beauty, but their stillness. In a world where travel often feels rushed and curated, York’s lesser-known alleys invite a slower rhythm. They ask you to pause, to look closely, to notice the way moss clings to a centuries-old doorframe or how a single beam of light illuminates a weathered coat of arms. These are not grand spectacles, but quiet revelations—small moments of connection between traveler and place that linger long after the trip ends.

The city’s medieval layout contributes to this sense of discovery. York was built for walking, not traffic, and its maze-like streets were never designed for ease of navigation. This complexity, once a matter of defense and daily life, now serves the curious wanderer. Each turn can reveal a new vista: a glimpse of the Minster’s spire framed by gabled roofs, a courtyard blooming with potted geraniums, or a sudden opening onto the river where swans glide silently beneath a stone arch. The joy is not in finding something specific, but in allowing the city to surprise you.

Finding Silence Above the City: Rooftop Perspectives

While many come to York to admire the Minster from ground level, few consider how the city looks from above—not from the official tower tours, but from quieter, less-traveled vantage points. The rooftops of York tell a different story, one of layered history, quiet resilience, and unexpected beauty. From these elevated views, the city unfolds like a hand-drawn map, with red-tiled roofs stretching in every direction, church spires rising like sentinels, and the River Ouse winding through it all like a silver thread.

One of the most accessible yet overlooked viewpoints is the upper path of the York City Walls near Monk Bar. While most tourists walk the lower sections, the elevated stretch here offers a sweeping panorama that includes both the historic center and the quieter residential neighborhoods beyond. At dawn, when the city is still wrapped in mist, the rooftops glow in soft gold and rose tones. The air is cool and still, and the only sounds are the distant chime of a church bell and the call of a lone crow. This is not the York of guidebooks—it is the York of quiet mornings and private moments.

Another hidden perch lies within the churchyard of St. Martin-cum-Gregory, near Micklegate. Though the church itself is modest, its surrounding walls provide a raised platform with a clear view toward the southwest. From here, you can see the Minster’s south transept framed by ancient yew trees, its stained glass catching the early light like a jewel. The path is open to the public, unmarked but permitted, and rarely crowded. It is a place for reflection as much as for photography.

For those willing to explore with care and respect, a few discreet public staircases and footbridges also offer elevated glimpses. The footpath leading from the Museum Gardens toward Lendal Bridge, for instance, climbs gently and opens onto a view of the river flanked by Georgian townhouses. It is not a dramatic overlook, but it is a peaceful one—ideal for watching the first boats of the day glide past or seeing the city wake up in stages. These rooftop perspectives do not require climbing or risk; they simply require timing and a willingness to look up.

River Ouse: A Mirror to Hidden York

The River Ouse is more than a geographical feature—it is a living mirror that reflects York’s past and present in shimmering detail. While many visitors cross its bridges or ride its riverboats, fewer take the time to walk its quieter banks, where the city reveals itself in double vision: once in stone, once in water. Along these less-traveled paths, the reflections of medieval walls, arched bridges, and cathedral spires ripple gently with the current, creating a dreamlike effect that feels both real and unreal.

One of the most serene stretches begins near Skeldergate Bridge and follows the river westward, away from the tourist core. Here, the path is lined with willow trees and dotted with benches, many of which face the water with unobstructed views. On a still morning, the surface of the Ouse becomes a perfect canvas, capturing the sky, the architecture, and the occasional heron standing motionless in the shallows. The light at this time of day—soft, diffused, golden—transforms even the most ordinary scene into something poetic.

Further along, near the historic Bishopthorpe Palace, the river bends gracefully, offering framed views of York’s skyline from a distance. This area is seldom crowded, and the sense of seclusion is profound. It is not uncommon to walk for ten minutes without seeing another soul, a rarity in any historic city. The sound of the water, the rustle of reeds, and the distant call of a moorhen create a natural soundtrack that drowns out the noise of the modern world.

Photographers and contemplative walkers alike will appreciate how the river changes with the seasons. In spring, the banks burst with daffodils and cherry blossoms; in autumn, the trees turn fiery red and gold, their leaves drifting slowly onto the water’s surface. Even in winter, when frost coats the railings and mist rises at dawn, there is a stark beauty to the scene. The Ouse does not demand attention—it simply waits, quietly, for those who know where to look.

Courtyards and Cloisters: Intimate Urban Oases

Behind unmarked doors and down narrow passages, York harbors a network of hidden courtyards—small, enclosed spaces that feel like secrets whispered between centuries. These are not grand plazas or public squares, but intimate pockets of calm tucked within the city’s dense fabric. Some are open to the public, others are stumbled upon by chance, but all share a sense of timelessness. They are places where ivy climbs ancient brickwork, where weathered stone arches frame the sky, and where the outside world seems to pause.

One such courtyard lies behind a modest gate on College Street, just a short walk from the Minster. Enter through a low archway, and you step into a space that feels centuries removed from the bustling cathedral grounds. The walls are covered in ivy and lichen, and a single wooden bench sits beneath a gnarled apple tree. In the center, a stone well—now dry—hints at a time when this was a working courtyard. The acoustics are remarkable: voices are softened, footsteps muffled, and the city’s noise reduced to a distant hum. It is a place designed for stillness.

Another hidden gem is the cloistered garden of Holy Trinity Church, located in Goodramgate. Though the church itself dates back to the 12th century, its garden is a quiet sanctuary rarely mentioned in guidebooks. Enclosed by high stone walls, it features a central lawn, a row of box hedges, and a collection of weathered headstones arranged with care. The atmosphere is reverent but not somber; it is a place of peace, where visitors often sit in silence or read a book beneath the shade of a copper beech.

These courtyards are not merely aesthetic—they serve as emotional counterpoints to the energy of the city. In a travel experience often dominated by movement and sightseeing, they offer stillness and reflection. They invite you to slow down, to notice the texture of a stone wall, the pattern of light through leaves, or the way a single flower grows from a crack in the pavement. They are not destinations in the traditional sense, but moments—fleeting, fragile, and deeply human.

The Role of Timing: Chasing Light, Not Crowds

In York, as in any historic city, timing is everything. The same alleyway that feels magical at sunrise can become a bottleneck of tour groups by mid-morning. The quiet bench by the river may be occupied by lunching tourists by noon. To experience the city’s hidden views, one must learn to move with the rhythm of light and solitude rather than the schedule of the average visitor. This means waking early, walking on weekdays, and embracing the subtle shifts that transform familiar places into something new.

Dawn is perhaps the most rewarding time to explore. Between 6:30 and 8:00 a.m., especially in spring and summer, the city is still and soft. The streets are washed in cool blue light, gradually warming as the sun rises above the rooftops. The Minster, when viewed from across the River Ouse at this hour, appears to float above the mist, its stone glowing with an inner warmth. Foot traffic is minimal, and even The Shambles—a usually packed attraction—feels hushed and intimate.

Rain, often seen as a travel inconvenience, can also enhance the experience. After a light shower, the cobbles glisten, the air is fresh, and the colors of the city deepen—timber frames look richer, greenery more vivid, and stone walls take on a velvety texture. The reflections in puddles add another layer of visual interest, turning ordinary streets into impressionist paintings. And because most tourists seek shelter indoors, the streets become unexpectedly empty, offering rare opportunities for unobstructed views and peaceful walks.

Weekdays, particularly Tuesday through Thursday, are also ideal for discovery. School and work schedules mean fewer families and tour groups, allowing for a more personal engagement with the city. A Wednesday morning stroll along the city walls, for instance, can feel like having York to yourself. The same is true for late afternoons in the off-season, when the light slants low and golden across the rooftops, casting long shadows that emphasize the city’s architectural depth.

Walking with Purpose: Routes for the Curious Traveler

To uncover York’s hidden views, you don’t need a detailed map or a guided tour—you need only a willingness to wander with attention. The most rewarding discoveries often come not from following a path, but from straying from it. This is not aimless wandering, but walking with purpose: observing, noticing, and responding to the subtle cues the city offers. It is a form of mindfulness in motion, where the journey matters more than the destination.

Begin by letting go of the checklist. Instead of rushing from one attraction to the next, allow yourself to be drawn by small details: a cat sunning itself on a windowsill, a patch of wall covered in centuries-old graffiti, a door painted an unexpected shade of blue. These are not distractions—they are invitations. Follow the cat down the alley, examine the graffiti, pause to admire the door. More than once, such moments have led travelers to hidden courtyards, unexpected vistas, or quiet benches with perfect river views.

Pay attention to architectural inconsistencies—the place where a modern building meets an ancient wall, the staircase that seems to lead nowhere, the archway that opens onto a tiny garden. These are often the thresholds between the known and the unknown. York’s layered history means that no street is ever exactly as it appears; behind a plain façade may lie a medieval courtyard, and beneath a modern shop front could be the remnants of a 14th-century hall.

Another useful principle is to walk slowly and look up. So much of York’s beauty is overhead: carved stone faces, ornate gables, rooftop sculptures, and the way ivy drapes from upper windows like green curtains. While most eyes are fixed on the ground or straight ahead, those who look up are rewarded with details others miss. A slow pace also allows you to notice changes in light, sound, and atmosphere—how a narrow lane suddenly feels cooler, or how the echo of footsteps changes when you enter a covered passage.

Finally, embrace detours. If a path looks intriguing, take it. If a gate is slightly ajar, pause and peer through. If a sign points to a place you’ve never heard of, go. York is a city that rewards curiosity, not efficiency. The best views are rarely the ones advertised—they are the ones you find by accident, then realize were waiting for you all along.

Why Hidden Views Matter: The Deeper Reward of Slow Travel

In an age of fast travel and instant photography, the act of seeking hidden views may seem like a small rebellion. But it is more than that—it is a return to the essence of what travel can be: a deep, personal encounter with a place. The quiet alley, the empty courtyard, the riverside bench at dawn—these are not just scenic moments. They are opportunities for presence, for mindfulness, for forming a connection that goes beyond the surface.

When we take the time to see York not as a list of attractions, but as a living, breathing city with layers of history and quiet beauty, we begin to understand it differently. We stop being observers and become participants. We notice how light changes with the seasons, how communities live alongside ancient walls, how a city can feel both timeless and alive. These subtle observations shape our memories more profoundly than any postcard-perfect photo.

Moreover, the practice of slow travel cultivates gratitude and awareness. It teaches us to appreciate not just the grand landmarks, but the small details—the way a door handle is worn smooth by centuries of hands, the sound of a blacksmith’s bell in a quiet street, the scent of rain on old stone. These are the textures of place, and they linger in the mind long after the trip is over.

York, with its rich history and intimate scale, is an ideal city for this kind of travel. It does not require grand gestures or expensive tours to reveal its secrets. It asks only that you walk slowly, look closely, and remain open to surprise. The hidden views are not hidden because they are inaccessible—they are hidden because most people do not take the time to see them.

So the next time you visit a city, resist the urge to rush. Let curiosity be your guide. Turn down the quiet street. Sit on the empty bench. Wait for the light to change. Because the most memorable moments of travel are rarely the ones you plan. They are the ones you discover—one hidden glance at a time.