You Won’t Believe What This Desert Town Celebrates—Culture in Swakopmund

Swakopmund isn’t just sand and sea—it’s a cultural heartbeat in the Namibian desert. I went expecting quiet streets and German colonial architecture, but found something wilder: music echoing at sunset, hands shaping clay in ancient ways, and stories told through dance. This coastal town blends indigenous heritage with coastal charm in ways you have to see to believe. It’s not just a stopover—it’s a story waiting to be lived. Nestled where the Atlantic Ocean brushes against the edge of the Namib Desert, Swakopmund exists in a space of quiet contradiction—cool fog rolling over sun-baked dunes, European facades framed by African skies, tradition moving steadily beneath modern life. What unfolds here is not a staged performance for visitors, but a living, breathing cultural rhythm shaped by resilience, memory, and creativity. This is a place where history is not buried but worn proudly, where art is not decoration but dialogue, and where every festival, craft, and melody tells the story of a people who have found beauty in survival.

Arrival: First Impressions of a Coastal Desert Town

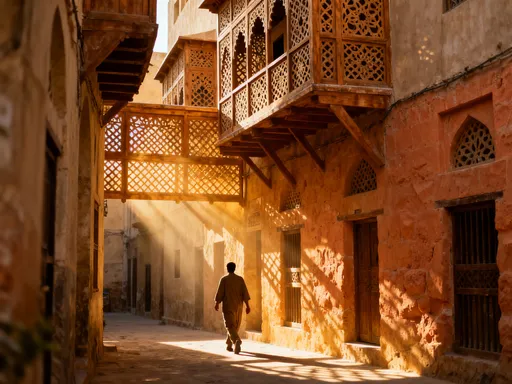

Stepping into Swakopmund feels like entering a dream painted in muted tones—silver skies, beige sand, and the deep blue of the Atlantic stretching endlessly. The air carries a salty chill, even in summer, as the cold Benguela Current sweeps up from the south, cloaking the coastline in morning fog. This is not the Africa many expect. There are no sweeping savannas here, no roaring lions—only the hush of wind over dunes and the soft crash of waves against a long, stony shore. The town’s layout is orderly, a legacy of its German colonial past, with wide avenues, gabled rooftops, and well-kept gardens that bloom defiantly in the arid air.

Yet beneath this calm surface lies a deeper story. Swakopmund was once a small port, a gateway for German settlers in the early 20th century. Today, it stands as a bridge—between desert and sea, past and present, tradition and modernity. The juxtaposition is striking: children in school uniforms walk past buildings with ornate German inscriptions, while street vendors sell roasted corn just blocks from cafés serving coffee and pretzels. The silence of the desert meets the rhythm of the ocean, and in that meeting, culture thrives. This unique environment shapes how people live, create, and remember. It is not a tourist town pretending to be authentic—it is a real community where identity is layered, complex, and proudly displayed.

Visitors often arrive curious, even skeptical, wondering what a desert town on the edge of nowhere could offer. But those who stay soon realize that Swakopmund’s magic isn’t in grand monuments or bustling markets—it’s in the quiet moments: an elder weaving a basket outside her home, a group of teenagers practicing dance steps near the waterfront, the scent of grilled meat drifting from a roadside stall at dusk. These are the signs of a culture alive, not preserved behind glass, but unfolding in real time. The town does not shout its history; it whispers it, and those who listen closely are rewarded.

The Pulse of Tradition: Indigenous Cultures in a Modern Town

Despite its colonial architecture and European influences, Swakopmund pulses with indigenous Namibian life. The Herero and Nama peoples, two of Namibia’s most historically significant communities, maintain a strong cultural presence here. Their traditions, shaped by centuries of resilience, are not relics of the past but living practices passed from generation to generation. In the town’s weekly markets, women in vibrant Herero dresses—elaborate gowns with high, horn-shaped hats—can be seen selling crafts, produce, and handmade textiles. These garments, rich in symbolism, are more than fashion; they are statements of identity, worn with pride in everyday life.

The Nama, descendants of the Khoikhoi, also contribute deeply to Swakopmund’s cultural fabric. Known for their pastoral heritage and intricate beadwork, they continue to speak Khoekhoegowab, a language still heard in homes and community gatherings. During local festivals, Nama elders lead storytelling sessions, recounting ancestral journeys, survival during colonial displacement, and the importance of land and livestock. These stories are not performed for tourists—they are shared within the community, reinforcing bonds and preserving wisdom.

What makes Swakopmund remarkable is how these traditions coexist with modern life. A young Nama woman might wear jeans and a T-shirt to work, then change into traditional dress for a family ceremony. A Herero man may drive a pickup truck to church, where hymns are sung in Otjiherero, the language of his ancestors. This blending is not forced; it is natural, born of necessity and pride. The colonial era brought hardship and erasure, but it did not extinguish culture. Instead, it deepened the resolve to preserve it. Today, cultural pride is visible in schools that teach indigenous languages, in community centers that host dance rehearsals, and in the quiet dignity of elders who remember what was almost lost.

Living Art: Craftsmanship and Creative Expression

Art in Swakopmund is not confined to galleries—it spills into streets, markets, and small workshops tucked between shops and cafés. Here, craftsmanship is not a hobby but a legacy. Local artisans work with wood, leather, clay, and beads, creating pieces that carry meaning far beyond their beauty. In the Woermann Street Market, rows of stalls display hand-carved animal figures, each shaped from African hardwoods like mopane and camel thorn. These are not mass-produced souvenirs; they are unique works, each bearing the mark of the artist’s hand and the spirit of the land.

One afternoon, I visited a small workshop on the edge of town, where a master carver named Johannes demonstrated his technique. With steady hands and a sharp chisel, he shaped a kudu from a block of ebony, explaining that each animal represents a story—sometimes a personal memory, sometimes a lesson from nature. “The wood speaks,” he said, “and we listen.” The scent of sawdust and oil filled the air, mingling with the rhythmic tapping of tools. Nearby, a young apprentice practiced carving smaller pieces, learning not just the skill but the patience and respect it demands.

Leatherwork and beadwork are equally revered. Nama women create intricate necklaces and bracelets using colored glass beads, a tradition that dates back to trade with European settlers. Each pattern holds meaning—some represent family lineage, others mark life events like marriage or birth. In another part of town, a cooperative of Herero women produces embroidered textiles, their stitches forming geometric designs that echo the patterns on their traditional dresses. These crafts are not made for display alone; they are worn, gifted, and used in ceremonies, ensuring that art remains woven into daily life.

Rhythms of the Coast: Music and Dance in Daily Life

If Swakopmund has a soul, it sings. Music is everywhere—not piped through speakers, but played by hand, shared in circles, passed down through memory. On weekend evenings, the jetty becomes a gathering place. Locals, young and old, bring drums, guitars, and the ramkie, a small, lute-like instrument with roots in Cape Malay music. The melodies are a blend of styles—Afrikaans folk tunes, German polka rhythms, and indigenous chants—reflecting the town’s layered history.

One evening, I joined a group near the water’s edge as they began to play. A man with a weathered face and a harmonica started a slow, haunting tune. Others joined in, clapping in rhythm, their voices rising in harmony. The lyrics mixed languages—some lines in German, others in Otjiherero, a few in English. It wasn’t rehearsed; it was spontaneous, heartfelt. Children danced barefoot on the wooden planks, their laughter blending with the music. A grandmother swayed gently, her hands moving as if guiding an invisible thread through time.

Dance, too, is a living tradition. In community halls and open squares, youth groups practice traditional movements—stomping feet, sweeping arms, gestures that mimic animals and ancestors. These dances are not performed for entertainment but as acts of remembrance and unity. During cultural events, entire families take part, passing down steps from grandparents to grandchildren. The rhythm is not just heard; it is felt in the chest, in the ground, in the pulse of the town itself. Music and dance here are not distractions from life—they are part of its fabric, binding people together across generations.

Festivals That Define a Community: When Swakopmund Comes Alive

Nowhere is Swakopmund’s spirit more visible than during its festivals. These are not tourist spectacles but community celebrations—moments when the town gathers to honor its roots, share its joys, and welcome others into its story. The National Arts Festival, held annually, transforms the waterfront into a vibrant stage. Colorful tents house art exhibitions, craft stalls, and performance spaces. The air fills with the scent of grilled meat, spices, and fresh-baked vetkoek—deep-fried dough served with savory fillings.

One afternoon during the festival, I watched as a group of Herero women took the stage in full traditional dress. Their movements were precise, graceful, each step a tribute to their heritage. Behind them, a choir sang in harmony, their voices rising over the sound of the waves. Nearby, children painted murals on large canvases, depicting desert landscapes, animals, and ancestral figures. Food stalls offered kapana—grilled beef strips—a beloved street food that brings people together across cultural lines.

Another highlight is the Swakopmund Moringa Festival, which celebrates local wellness traditions and sustainable living. While not strictly cultural in the artistic sense, it reflects a growing pride in indigenous knowledge—herbal remedies, natural dyes, and traditional farming methods. Workshops teach visitors how to use moringa, a nutrient-rich plant long used in rural Namibian communities. These events do more than entertain; they educate, connect, and empower. They show that culture is not static—it evolves, adapts, and finds new ways to thrive.

Colonial Echoes and Cultural Fusion: The German-Namibian Blend

Swakopmund cannot be understood without acknowledging its colonial past. The German influence is visible in its architecture—half-timbered houses, a neo-Gothic church, and the iconic Swakopmund Lighthouse. German is still spoken by some residents, and bilingual signs appear throughout the town. Bakeries display brötchen and strudel in their windows, and Sunday mornings often bring the smell of fresh pretzels drifting through the streets. But this is not a town frozen in nostalgia. Instead, it has redefined its colonial legacy, blending it with African identity in ways that feel authentic, not forced.

In a small café near the market, I ordered coffee and a piece of omalila—pumpkin cooked with maize meal, a staple in many Namibian homes. The menu was written in both German and English, and the waitress, a young Nama woman, greeted me in three languages. This kind of fusion is common: a German-style house painted in bright Herero colors, a church choir singing hymns in Otjiherero and German, a school play that mixes colonial history with indigenous storytelling. The past is not erased, but it is no longer dominant. It is one thread in a larger tapestry.

This duality is not always comfortable—there are still conversations about land, memory, and justice. But Swakopmund chooses dialogue over division. Art exhibitions explore colonial history with honesty. Community projects bring together descendants of settlers and indigenous families to work on shared goals. The town does not pretend the past was fair, but it refuses to let history dictate the future. In its streets, its food, its music, and its daily life, Swakopmund shows what cultural fusion can look like when it is rooted in respect, not domination.

Beyond the Surface: How to Truly Experience Swakopmund’s Culture

To experience Swakopmund’s culture, one must move beyond the postcard views and guided tours. It requires slowing down, listening, and engaging with intention. Start by visiting local galleries and craft markets, but don’t just buy—ask questions. Learn the names of the artists, the meanings behind their work, the stories they carry. Attend a community event or festival, not as a spectator, but as a guest. Sit with locals, share a meal, accept a cup of tea. These small acts of connection matter more than any checklist of attractions.

Timing your visit around cultural events increases the chance of deeper immersion. The National Arts Festival, usually held in spring, offers a rich program of performances, workshops, and exhibitions. The Moringa Festival, in summer, provides insight into traditional wellness practices. Even outside these times, daily life offers opportunities: a church service with multilingual hymns, a street musician playing a ramkie tune, a grandmother teaching her granddaughter to bead. These moments are not staged—they are real, unfiltered, and deeply meaningful.

Most importantly, approach Swakopmund with respect and humility. Culture is not a backdrop for photos; it is a way of life. Avoid treating traditions as curiosities or performances. Instead, recognize the resilience behind them—the centuries of survival, adaptation, and pride. Support local initiatives, buy directly from artisans, and choose accommodations and tours that prioritize community benefit. When you walk through Swakopmund, do so with open eyes and an open heart. Let the town reveal itself not as a destination, but as a living story.

Swakopmund’s culture isn’t performed for tourists—it’s lived, shaped by desert winds and ocean tides, by memory and reinvention. To experience it is to listen closely, walk slowly, and let the town reveal itself not as a relic, but as a rhythm still being written. The real journey begins when you stop looking and start feeling.