Santorini Bites: A Cultural Feast You Can Taste

Walking through Santorini, I didn’t just see whitewashed villages and sunset views—I tasted them. Every bite of creamy fava, every forkful of tomato keftedes, told a story older than the caldera itself. This island doesn’t just feed you; it invites you into centuries of tradition, where food is memory, land is legacy, and meals are shared like prayers. The volcanic soil underfoot, the sun-baked terraces, the salt-kissed air—all shape what ends up on the plate. If you think Santorini is just a pretty view, wait until you taste what it truly offers. Here, cuisine is not an accessory to the journey. It is the journey.

The Heartbeat of Santorini: Food as Cultural Identity

Santorini’s cuisine is not born of luxury but of resilience. The island’s dramatic landscape—carved by ancient eruptions, shaped by wind and drought—has dictated a way of eating that is as practical as it is profound. With little rainfall, poor soil by conventional standards, and relentless sunlight, farming here is an act of defiance. Yet from these constraints, a rich culinary identity has emerged. The concept of *terroir*, often reserved for fine wine, applies equally to every dish on this Aegean isle. What grows here grows differently nowhere else, shaped by the same volcanic forces that formed the caldera over 3,600 years ago.

The island’s unique geology enriches its produce with minerals, lending a depth of flavor that cannot be replicated. Assyrtiko grapes thrive in the ashen soil, their roots drawing sustenance from layers of pumice and lava. Cherry tomatoes, small and bursting with sweetness, develop their intensity under the hot sun, their skins taut from conserving every drop of moisture. Capers, wild and pungent, cling to rocky crevices, flourishing where few other plants dare. These are not just ingredients—they are survivors, much like the people who have cultivated them for generations.

This relationship between land and plate is not accidental. For centuries, Santorinians have adapted their diets to what the earth provides. When water was scarce, they preserved tomatoes into thick pastes and sun-dried them on rooftops. When legumes were more reliable than meat, they perfected fava—a smooth puree made from yellow split peas native to the island. Even today, these traditions endure not as nostalgic relics but as living practices. To eat in Santorini is to participate in a dialogue between past and present, between hardship and ingenuity. It is to understand that food here is not merely consumed; it is honored.

From Vineyards to Tables: The Role of Assyrtiko in Daily Life

No element of Santorini’s cuisine captures its spirit more vividly than Assyrtiko wine. This white grape, almost exclusively grown on the island, is a marvel of adaptation. Cultivated in low, basket-shaped vines called *kouloura*, it hugs the ground to avoid the strong Meltemi winds and conserve moisture. The vines twist into circles, their leaves shielding the grapes from the sun, creating a microclimate that allows the fruit to ripen slowly and evenly. This ancient method, passed down for generations, is not merely agricultural—it is ancestral.

The resulting wine is a reflection of the island itself: crisp, bright, and layered with minerality. Assyrtiko carries the taste of volcanic rock, a subtle salinity that lingers on the palate. Its high acidity makes it both refreshing and age-worthy, capable of pairing with everything from grilled octopus to sharp local cheeses. But beyond its sensory appeal, Assyrtiko holds a sacred place in daily life. It is not reserved for special occasions. Instead, it appears at nearly every meal, poured generously from a carafe as naturally as water.

Visitors seeking an authentic experience will find it not in glossy wine tours but in family-run wineries tucked into the hillsides of Exo Gonia or Megalochori. Here, owners speak with quiet pride about their craft, offering tastings on shaded patios where the breeze carries the scent of thyme and sea. A glass of Assyrtiko at dusk, accompanied by a small plate of olives, grilled zucchini, and dakos (a barley rusk topped with tomato and feta), is not a performance for tourists—it is a ritual. It is the way islanders have welcomed one another for generations, a gesture of warmth and continuity.

Walking through these vineyards, one senses the deep connection between stewardship and sustenance. Each row of vines has been tended by hand, pruned with care, harvested with gratitude. To drink Assyrtiko is to taste the labor of many hands and the wisdom of many seasons. It is not just wine. It is liquid memory.

Street Eats with Soul: Discovering Tomato Keftedes and Fava

Among the most beloved flavors of Santorini are two humble dishes that speak volumes about its history: tomato keftedes and fava. Tomato keftedes, golden fritters made from the island’s sweet cherry tomatoes, are a celebration of abundance. When the harvest peaks in late summer, families gather the ripest tomatoes, grate them by hand, mix them with herbs and a touch of flour, then fry them until crisp. The result is a savory bite that crackles with heat and bursts with tangy sweetness—a taste of sunshine captured in oil.

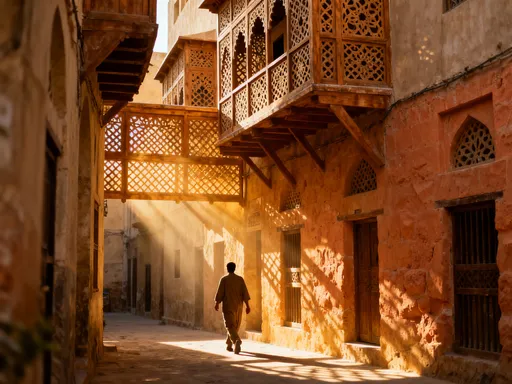

These fritters originated as a way to use surplus tomatoes before they spoiled. There was no waste in traditional Santorinian kitchens. What could not be eaten fresh was transformed—dried, preserved, or fried. Today, the best keftedes are still made this way, in small tavernas where the oil sizzles in copper pans and the aroma draws people from the narrow alleyways. In villages like Pyrgos or Emporio, you might see an elder woman at her doorstep, flipping batches with practiced ease, her hands moving without thought. There is no menu board, no online reservation. You simply arrive, sit, and wait—because good food cannot be rushed.

Equally iconic is fava, a creamy yellow puree that has been a staple since ancient times. Despite its name, it is not made from fava beans but from a local variety of yellow split peas that grow only in Santorini’s volcanic soil. Slow-cooked for hours with onions and bay leaves, then blended into a velvety spread, fava is served warm, drizzled with olive oil and a sprinkle of capers. It is simple, nourishing, and deeply satisfying—a dish born of necessity that has become a symbol of comfort.

To eat fava in Santorini is to taste history. Archaeological evidence suggests that this legume was cultivated on the island as far back as the Bronze Age. It sustained families through lean years and fed communities during times of hardship. Today, it remains a fixture on taverna tables, often accompanied by fresh bread and a glass of white wine. The contrast of textures—the smoothness of the puree, the crunch of bread, the brininess of capers—creates a harmony that is both rustic and refined. These are not gourmet inventions. They are the quiet masterpieces of a people who know how to make the most of what they have.

The Ritual of the Taverna: More Than Just a Meal

In Santorini, dining is not an event. It is an experience—one that unfolds slowly, without agenda. The taverna is more than a restaurant; it is a social institution, a place where time expands and connections deepen. Meals here often begin late and end later, stretching across hours as plates are shared, stories are told, and laughter rises above the clink of glasses. There is no pressure to vacate a table. No one checks their watch. Instead, there is a collective understanding that good food deserves good company and that both are worth savoring.

This philosophy is rooted in *meraki*—a Greek concept that describes doing something with soul, creativity, and love. When a taverna owner greets you by name, when a cook brings an extra dish “just because,” when a server insists you try the figs from their grandmother’s tree, you are witnessing *meraki* in action. It is not performance. It is presence. It is the belief that feeding someone is an act of care, not just commerce.

Authentic tavernas are often unassuming—family-run establishments with handwritten menus that change daily based on what’s fresh. In Akrotiri or Messaria, you might find a small courtyard shaded by grapevines, tables set close together, children weaving between them. The menu offers little description: “grilled fish,” “seasonal greens,” “home-baked pie.” Yet each dish carries the mark of intention. The greens are foraged from nearby hills. The fish was caught that morning. The pie was rolled that afternoon by hands that have done it for decades.

Contrast this with the crowded restaurants in Fira or Oia, where tables face the sunset and prices rise with the view. While some offer quality food, many prioritize spectacle over substance. The experience is transactional—meals served quickly, tables turned rapidly. In the quieter villages, however, the rhythm is different. Here, a meal might conclude with a shot of *rakomelo*, a warm drink made from raki infused with honey and cinnamon, offered freely as a gesture of hospitality. It is not on the menu. It is simply how things are done.

Cooking with the Land: Lessons from Local Kitchens

For visitors who wish to go deeper, Santorini offers rare opportunities to step inside local kitchens and learn directly from those who keep the traditions alive. These are not staged cooking demonstrations but intimate, hands-on experiences led by islanders—often grandmothers, aunts, or home cooks with decades of practice. In a sunlit kitchen in Megalochori, you might knead dough for *kopania*, a dense, unsalted bread baked in wood-fired ovens. In a vineyard home, you could help grind capers with a stone mortar, their sharp aroma filling the air.

These classes are not about perfection. They are about connection. You might learn to fold dolmades—grape leaves stuffed with rice, pine nuts, and herbs—using techniques passed down through generations. The instructor may not speak fluent English, but her hands move with clarity, showing how to place the filling, how to roll tightly but gently. She might hum a tune as she works, a song from her childhood. There is no rush, no grading. Only the quiet rhythm of doing.

What makes these experiences so powerful is their authenticity. There are no branded aprons, no commercial recipes. You are not learning to replicate a dish for dinner parties back home. You are learning to respect a way of life. One woman in Exo Gonia teaches her students to bake *fanouropita*, a simple spice cake offered to Saint Fanourios as a thank-you for favors granted. She explains that the cake must be shared, never kept for oneself—a lesson in generosity as much as in baking.

These kitchen gatherings are acts of cultural preservation. As younger generations move to cities or pursue other careers, the knowledge of traditional cooking risks fading. By inviting visitors to participate, elders ensure that these practices are not forgotten. To roll a dolma, to stir a pot of fava, to press a grape in a stone press—is to become a temporary keeper of memory. It is one of the most meaningful ways to honor the island.

Beyond the Plate: How Food Shapes Festivals and Seasons

On Santorini, the calendar is marked not by months but by harvests and holy days. Food is not just eaten—it is celebrated, blessed, shared in rhythm with the seasons. In late summer, when cherry tomatoes reach their peak, villages host feasts to honor the harvest. Families gather in courtyards, where long tables are set with platters of keftedes, sun-dried tomatoes, and fresh cheeses. Music plays, often live, with locals dancing the syrtos under string lights. These gatherings, known as *panigiria*, are open to all, including respectful visitors who come not as spectators but as participants.

In August, the Feast of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary brings communities together for one of the island’s most important religious events. Churches are adorned with flowers, processions wind through the streets, and tables overflow with food. Lamb is roasted slowly over coals, potatoes are baked in ash, and wine flows freely. The meal is not rushed. It is a communal offering, a way of giving thanks for the year’s blessings. Even in modern times, many families adhere to traditional fasting periods before the feast, making the eventual celebration all the more meaningful.

Easter, too, is a culinary milestone. After weeks of Lenten abstinence, the Sunday roast of lamb is a moment of joy and renewal. Families rise before dawn to prepare the fire, seasoning the meat with rosemary, garlic, and lemon. The scent fills the neighborhood, drawing neighbors into conversation. Children run between houses, baskets in hand, collecting dyed eggs and sweet breads. The meal lasts for hours, punctuated by toasts and stories. It is not just about eating. It is about belonging.

These traditions reveal a truth that runs deep in Santorinian life: food is never separate from faith, family, or the land. It is the thread that ties them together. For visitors, participating in a festival is not about taking pictures or checking a box. It is about slowing down, showing respect, and allowing oneself to be welcomed. A simple “kalispera” (good evening), a small gift of wine, a willingness to sit and listen—these gestures open doors that might otherwise remain closed.

Eating with Purpose: Supporting Authentic Santorini

As tourism grows, so does the risk of losing what makes Santorini’s food culture special. Chain restaurants, inflated prices, and generic menus threaten the authenticity that draws so many in the first place. But travelers have the power to protect it. By making mindful choices, visitors can support the families and farmers who sustain the island’s culinary heritage. The first step is knowing where to go—and where not to.

Look beyond the postcard-perfect terraces of Fira and Oia. Venture into inland villages like Megalochori, Pyrgos, or Emporio, where family-run tavernas serve food grown in their own gardens. These places often have no website, no online reviews, and no English menu. But they have heart. Ask locals for recommendations. Follow the scent of grilled meat or fresh bread. Arrive early, as many close by mid-afternoon. Be patient. Let the meal unfold at its own pace.

Seasonality matters. A restaurant that offers strawberries in December or watermelon in March is not using local produce. True Santorinian cuisine changes with the calendar. In spring, look for wild greens, artichokes, and fresh herbs. In summer, savor tomatoes, zucchini flowers, and grilled sardines. In autumn, enjoy figs, grapes, and new wine. In winter, find slow-cooked stews and preserved foods. Menus that reflect this rhythm are likely to be more authentic.

Consider visiting in the shoulder seasons—April to early June, or September to October. The weather remains pleasant, the sea is warm, and the island breathes more easily. You’ll find shorter lines, lower prices, and a closer view of daily life. Walk the trail from Oia to Ammoudi Bay, then stop at a fisherman’s hut for grilled octopus and a glass of Assyrtiko. Take a slow ferry instead of a speedboat. Stay in a family-owned guesthouse where the host offers breakfast from their garden.

To eat mindfully in Santorini is to engage with the island on its own terms. It is to honor the hands that grow, cook, and serve. It is to carry home not just memories, but a deeper understanding of what it means to live in harmony with the land. The flavors will linger long after the tan fades. And perhaps, in your own kitchen, you’ll find yourself reaching for capers, or slow-cooking peas, or toasting a glass of white wine—not just for taste, but for connection. That is the true feast. That is Santorini, on the tongue and in the soul.